ID:entity Self: Perception and Reality

I stepped out of my comfort zone and into the future when I visited CAM Raleigh last weekend for the opening of ID:Entity at the Contemporary Art Museum of Raleigh. The exhibition features interactive work by artists and faculty associated with the NC State University Departments of Art+ Design, and with the Ph.D. program in Communication, Rhetoric and Digital Media. I was there, particularly, to see a piece by my oldest son, David Millsaps. David is a digital media consultant and interface designer and over the past several years has created several large scale digital works of art either alone or collaboratively.

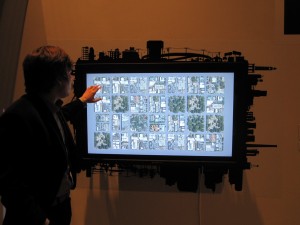

His wall piece, Routine, mimics a version of Raleigh, gridded with streets, which, when touched by the viewer, morphs into more developed, or less developed– with more trees or less, and more buildings or fewer. The viewer makes decisions about the way the city should look. A cluster of fireflies working from a flocking algorithm becomes an icon representing humankind and its interaction with the built environment. He imagines the fireflies as having a “hive mentality” like mankind connected by technology.

A week later I had a chance to sit down with David and talk late into the night about his experience making this work. It was interesting to compare traditional media to the way artists in digital media work. The news release about the show refers to the artists as “pioneers in new media arts”. In talking to David it was clear to me that indeed he is exploring a new continent. What I do in my studio is a variation of the same processes that artists have used for thousands of years. What David does is, by comparison, to step out into a kind of wild jungle of unexplored, unmapped territory.

He talked to me about the difficulties he found in creating this work. He related how the properties of a software application are able to be replicated. But they change based on the tools they are running on. He talked about how it is new science and how it is thus impossible to estimate the time it will take to achieve a goal. David lamented that he can set a goal and he may or may not get there. In the case of Routine, he created the work on a computer that was more powerful than the equipment used to transmit it, and ended up having to ratchet down the parameters of the piece to fit the presentation tools available.

David also expressed surprise in observing the way people interacted with the piece. The piece has a sign inviting the viewer to touch the screen. He found people reaching out to touch the sign instead of the piece. This illustrates, for me, a bit of the disconnect between people like David who are at home– I mean AT HOME, in a digital world, and the rest of us who live in a world more like the previous thousand years.

When I stepped into this ephemeral exhibition, loaded with wall projections, constantly moving and morphing, I found myself longing for the fatness of paint, the grain of wood, the traditional visceral, sensual materials of the past. People like David, so accustomed to the digital vocabulary don’t have that sense of loss.

McArthur Freeman seemed to me to bridge the divide with his series of small heads. A brilliant draftsman and painter, McArthur has, of late, been exploring the union of his traditional images and technology. In ID:entity the characters he has created have been generated by technology that renders a three dimensional object from a drawing. The heads are laminates of many planes assembled to create the final image. The heads have a voluptuousness and presence that loops back to traditional art.

I started to make a case, in my late night talk with David, that this technological art was somewhat removed from human emotion. I wanted to spin a line of reasoning that it was cold and detached, born as it is from a machine, without evidence of the human hand. But I only got a couple of sentences out before remembering that I had found the exhibition, as a whole, to be very senusous, in its own way. Much of it projected onto a screen or wall, bearing a stronger resemblance to a movie or television program than to a painting, it had a kind of subtle sensuality, arriving from some mental place instead of from the sense of touch. It bore the mark, as does any good work, of thought and intensive labor, of energy concentrated in a vehicle set out for our contemplation. Only in this interactive exhibition, over and over, the viewer was invited to enter into the work and become a part of it.

Recent Comments